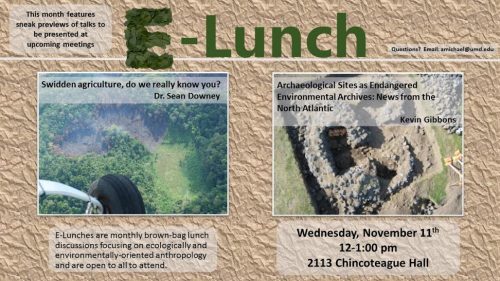

Swidden agriculture, do we really know you?

Sean Downey, University of Maryland

Swidden agriculture is a prototype coupled human-natural system. It involves annual forest clearing, planting, and harvesting when human agency asserts control over ecosystems to provide sustenance. These annual cycles are nested within decadal cycles of forest regrowth when natural ecosystem services dominate. Thus, swidden systems are fundamentally anthropogenic. In 1963, Clifford Geertz asked a simple question: what makes swidden work? Since then, anthropologists have studied swidden extensively and a formerly strange form of agriculture has now become familiar. Remarkably, scholarly consensus within anthropology suggests swidden can promote biodiversity and resilience, based on intimate knowledge of local environments, well-adapted cultigens, local ecological knowledge, local institutions, social norms, and belief systems. Yet, swidden is still widely regarded by many outside the academe as inefficient and unsustainable, leading to calls for alternative 'sustainable' livelihoods such as wage labor, craft production, or tourism. In this talk, I suggest that it is time to make swidden strange again. One reason appreciation for swidden's potential has not grown beyond a subset of scholarly fields is because we still know very little about how specific social and environmental mechanisms of swidden interact, how a sustainable subsistence could emerge, and its limits especially with regard to social and environmental factors: we still do not know much about 'how swidden works'. Drawing on insights from complex adaptive systems and emergence, and my own fieldwork with Q'eqchi' Maya communities in southern Belize, I will explain how a sustainable and resilient swidden subsistence system could emerge.

Archaeological Sites as Endangered Environmental Archives: News from the North Atlantic

Kevin S. Gibbons and George Hambrecht, University of Maryland

The North Atlantic Biocultural Organisation (NABO) is a multidisciplinary research network that has been coordinating an integrated historical ecology research program across the North Atlantic region for over two decades. Like much of the globe, this sub-Arctic region is experiencing increasingly rapid environmental change that is generating profound threats to cultural heritage and archaeological sites. Beyond the need to protect cultural heritage from these threats due to their inherent cultural, social, and economic value, these sites also contain data that represent the results of completed long-term resource management experiments operating within past social-ecological systems. Historical ecology work done in the North Atlantic views archaeological data as distributed observation networks of human ecodynamics in the past that can be mobilized to help understand processes of change and contribute baseline data for resource management decisions impacted by anthropogenic climate change.

This paper introduces current research that illustrates the wide-ranging potential of an integrated historical ecology approach. Methods ranging from palaeogenetics to stable isotope analysis are being employed to tackle questions relating to climate change and the traditional ecological knowledge driving local resource interactions and management.