Event Date and Time

Location

Woods Hall, Room 1102

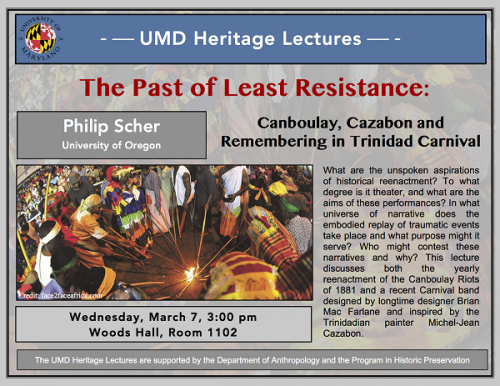

Please join us for the talk "The Past of Least Resistance: Canboulay, Cazabon and Remembering in Trinidad Carnival" given by Philip W. Scher, Divisional Dean for Social Sciences and Professor of Anthropology and Folklore and Public Culture at the University of Oregon. The talk will take place Wednesday, March 7 at 3:00 PM in Woods Hall, Room 1102.

Dr. Scher is the fourth speaker for the 2017-2018 UMD Heritage Lectures series, co-sponsored by the Department of Anthropology and the Program in Historic Preservation. His research examines the politics of heritage and cultural identity, popular and public culture, tourism and transnationalism, in the Caribbean and Caribbean diaspora. His published works include Carnival and the Formation of a Caribbean Transnation (Florida, 2003), and Trinidad Carnival: The Cultural Politics of a Transnational Festival (co-edited with Garth L. Green, Indiana, 2007). He is the author of the forthcoming book An Economy of Souls: The Politics of Heritage in the Contemporary Caribbean.

Abstract:

What are the unspoken aspirations of historical reenactment? To what degree is it theater, and what are the aims of these performances? In what universe of narratives does the embodied replay of traumatic events take place and what purpose might it serve? Who might contest those narratives and why? The following essay discusses both the yearly reenactment of the Canboulay Riots of 1881 and a recent carnival band designed by longtime designer Brian Mac Farlane and inspired by the Trinidadian painter Michel-Jean Cazabon. This Carnival band, based on the colonial paintings of a celebrated Trinidadian artist of the early 19th century, were met with controversy, as they depicted master slave relationships in carnival costume form. I compare these examples in order to pursue two ideas simultaneously. The first is a meditation on the role of the historical event(s) in Trinidad in relation to a broader reproduction of general historical narratives especially in relation to shifting notions of Carnival. The second is to situate these relationships with regard to conceptions of contested memory in Carnival, and specifically to the objectives of the state. In exploring these ideas, I note that both the reenactment and the masquerade performance belie a somewhat uncertain relationship that Trinidad carnival has with broader conceptions of revolution and emancipation in the anglophone Caribbean.